Five-Day Fast

November 09, 2020

Last week, from Monday 2 November to Friday 6 November 2020, I did a self-run writing retreat at home, during which I also fasted.

For those five days I didn’t eat, speak, or use screens. I just read, wrote, meditated, exercised, explored, and slept.

I found it quite intense. Several people have expressed curiosity about my experience so I’m writing here to document it and to decompress.

If you’re interested in this topic, you may also be interested in my upcoming Asceticism salon, where we’ll discuss this and related issues. The salon partially motivated me to do this fast.

As this article got a bit long, here are some shortcuts:

- The Rules

- What did you do?

- Why did you do this?

- Fasting

- Insulin usage

- How did you track stuff?

- What did you get out of it?

Didn’t you do this before?

In April I did something sort of similar (a five day Zoom meditation retreat) which you can read about here.

During that retreat I found that there is, for me, a trade-off between writing and meditation — they tax my brain in similar ways. That time, I focused on meditation. This time, I very much focused on writing.

I also ate once per day on that retreat, whereas this time I was basically water fasting for the duration. (Water fasting means you’re not eating, only drinking water.)

What were the rules?

From after dinner on Sunday night to dinner on Friday night, I decided that…

- I would not eat anything.

- I would not drink anything other than water.

- I would not use screens.

- I would not say anything.

- I would not listen to anything.

- I would not buy anything.

Did you break any of the rules?

In short, no.

The longer version is yes, but barely. I followed rule #1 to the letter, and the rest with very mild tweaks, some of which were out of my control.

Did you eat anything?

I didn’t eat anything at all. As a Type I diabetic, this was a bit tricky at times; in the end, I was using very little insulin (see below).

Did you drink anything other than water?

Yes. I decided “I will not drink anything other than water and one cup of black coffee per day.”

On a normal day I would drink 2–3 cups. I changed the rule after the first day, during which I fell asleep four times. I probably could have pushed through and gotten used to it, but I decided that since reducing caffeine wasn’t one of my goals, and I know from previous experience that coffee doesn’t affect my insulin levels or hunger, that I should just try to stay awake for more of the experience rather than to doze my way through the week.

I did need to drink a lot of water. I normally drink a lot, but when fasting seem to need even more.

Did you use screens?

No, none that I hadn’t planned to.

I didn’t use any smartphone or computer screens. I did use my Kindle as planned. I don’t find that it breaks concentration/mindfulness or distracts me. Most of the books I have on there are fairly heavy anyway, so it’s not very tempting to switch.

These days, medical devices for diabetes have annoying smartphone-like screens, which I had to use. They were better when they were liquid-crystal; their batteries lasted longer. Anyway, I knew I’d have to look at these.

Apart from those, I didn’t use screens.

Did you speak?

Yes, I did occasionally speak.

I live in London, where it is impossible to walk or stand near people (or even 2m away from people) without saying “sorry” and “thank you” a lot. Apologies in particular are a part of the culture which it would be rude to forego entirely. If intoned in proper British fashion, they should sound like an apology for your very existence, in addition to the apology for wherever you happened to be walking or standing. I sometimes did this without thinking.

On the third day, at midday, precisely halfway through the retreat, I also spoke to someone, by accident. This was unplanned and more-or-less unavoidable; I was in our garden and a builder called down to me from another flat. I could not have ignored him without being rude, and in any case I did not think to do so until after I had already responded. He might have needed something. Instead, he wanted to chat (to be fair, in 2020, maybe he just needed that).

We talked about London (we had both been here around a decade, give or take). He asked about California (I’m from Orange County) and I asked about Romania (he was from Satu Mare). As soon as I was able to do so politely, I went back inside. The conversation lasted less than five minutes.

I also wrote letters, to my wife and to a few other friends. This was as planned.

Did you listen to anything?

I normally listen to a lot of podcasts, audiobooks, and music. I didn’t listen to podcasts or audiobooks at all. I didn’t listen to any music, at least not intentionally. Though there were two ways I did so unintentionally.

One was just from walking around London:

- At Lauderdale House, when I walked by, there was a jaunty piano tune emanating from an upper window, perhaps the same one from which Nell Gwyn was reputed to have dangled the young Earl of Burford.

- In Queen’s Wood, I walked into what appeared to be the making of a Spanish music video.

It sounded like a love song, or least I caught the word “corazón” before they stopped playing to let me pass (unnecessarily; I would have waited, but they had already stopped).

In the silence of my existence for the remainder of the week, I had a few notes of that unfamiliar Spanish song stuck in my head.

Which brings me to the other unintentional way I listened to music: I had whole albums playing in my head from memory. This got more intense as the week went on.

Did you buy anything?

No, although I did mention that a pen of mine had run out (a Pilot G-Tec-C4 which is perfect for underlining), in a letter I wrote to my partner. She ordered it and it arrived during the retreat. In my defence, I did not expect her to do this immediately, nor for it to arrive before the retreat had ended, but she did and we received it.

What did you do instead?

- I read books and Kindle (25 hours).

- I wrote by hand (17 hours).

- I exercised (10 hours).

- I meditated (7 hours).

- I explored my area of London with a 2007 mini A-Z.

People looked at me strangely when they saw me standing around, leafing through this.

Why did you do this?

I’ll give ten reasons:

- I’ve been feeling really uncertain lately and wanted to decide on a plan (which I did; see below).

- I’m hosting an Interintellect salon on Asceticism on 19 November (information here if you’re interested), so it seemed an appropriate time to do it.

- I wanted to see whether time slowed down. (It did.) Lots of people are working on objectively extending life; why not work on subjectively slowing the passage of time?

- I’m interested in the phenomenology of extreme experiences generally.

- I wanted to try a Digital Minimalism-style hard reset on technology and distractions.

- I wanted to see how much I could write in that time if I was entirely undistracted, and whether handwriting significantly differs from typing.

- I wanted to burn the first week of the new UK lockdown doing something other than doomscrolling (but see below).

- For the past three years I have stopped drinking alcohol for November, and I wanted to kickstart that process.

- I wanted to see if I could do it.

- I wanted to lose some weight.

Was this to miss the election?

No, that was just an unexpected bonus. I planned it without thinking about that, and it didn’t occur to me until a few days in that I would not hear about it.

Why do you do Dry November?

As I said in #8 above, I’ve taken off a month from drinking for the past three years, a practice I think of as “Dry November” by way of analogy with “Dry January.” I have no idea whether anyone else does this.

I’ve done Dry January before too, and I understand why people do it, to reset after the holidays. But I also like the idea of resetting before the holidays. In 2017, I had a particularly heavy November, after which it was hard to keep up that level of momentum in December. So in 2018 I tried Dry November and it’s become a bit of a tradition.

Did you burn a week of lockdown?

Sadly, no. If anything I prolonged the lockdown for myself.

I’m in the UK we’re now in the second lockdown of 2020. I was not happy going into the first one. The April retreat made a big difference.

I was also concerned about getting anxious during this lockdown. I expected it to start on Saturday 31 October, so by going on retreat, I’d miss the first week. Instead, the announcement on the 31st was that the lockdown would start on the 5th November. This means I missed the last week of “freedom” (if such a thing can be said to exist this year). This was annoying, but I thought I’d better to stick to what I’d planned, since I somehow felt I was mentally prepared.

Fasting

Weren’t you hungry?

Yes, at times. The first three days were surprisingly easy, though as I said above, I’m used to fasting.

The worst time was on Thursday, around 5pm (92 hours in), when I faced debilitating hunger, the worst of my life. I knew it would come at some point, and I wanted to wait it out. I had already walked 8 miles that day, so I did not particularly feel like exercising (which I find reduces hunger). So I just kept reading.

It was not exactly painful, but it was extremely intense. Since we had a fully-stocked fridge, I was not entirely sure I would be able to control myself. What was most surprising is that it went away after about twenty minutes, on its own, without my moving or doing anything. It didn’t come back.

Did you miss food?

Yes, and that’s different from being hungry. I missed food and I missed cooking. I also fantasised and dreamt about food, which I never do, and if I made the mistake of imagining food, I would salivate intensely. This is not a normal thing for me; I’m fairly stoic when it comes to food.

George Orwell, in his amazing Down and Out in Paris and London:

This was a blow. I was horribly disappointed, for I had allowed my belly to expect food, a great mistake when one is hungry.

I missed cooking because I love the ritual and the chemistry-experiment feeling that it always has for me. I find cooking to be an absolute pleasure, and therapeutic. It was a big relief to cook on Friday.

Actually, that may have been my most Stoic moment of the week, another test which I wasn’t sure whether I would pass: On the fifth day of the fast, I prepared and cooked a stew to go into the slow cooker, i.e., I dealt with a bunch of food that I wouldn’t be able to eat for another five or six hours and was in and out of the fridge. Somehow I managed, and I felt a bit proud about this. The stew was good.

Why did you fast? Why not just meditate?

I fast anyway. And I had been wanting to try a longer fast for a while, just to see what they are like.

I suppose reasons to try this were:

-

Mental clarity, which I invariably get on shorter fasts.

-

My upcoming Asceticism salon.

-

Rumoured benefits of autophagy.

-

I read Fung/Moore’s The Complete Guide to Fasting last year and enjoyed it.

Since then I had been wanting to try a longer fast. I recommend that book if you’re curious about fasting.

-

Mark O’Connell wrote a great piece called “Splendid Isolation” recently which also made me want to do a fast without screens.

-

I’ve been wondering whether fasting might improve neuroplasticity.

I have no way of directly verifying that but I thought there might be some phenomenological ways. (This was inconclusive.)

Have you fasted this long before?

No, nowhere near. I frequently fast 24 hours, but my longest fast before this one was maybe 2.5 days (~60 hours). This fast was 5 days (120 hours), or double the length of my previous longest fast.

Was it harder than a short fast?

For me, yes, dramatically so, but maybe that’s just because I’m so used to short fasts.

Fung/Moore say it should get easier after the second day:

The majority of people find day 2 of an extended fast to be the most difficult in terms of hunger.

After day 2, many people describe a gradual lessening and then a total elimination of hunger. (Some have hypothesized that this effect is due to the high number of ketone bodies that begin circulating after a couple of days.)

Orwell heard that it should get easier after three days:

We went several days on dry bread, and then I was two and a half days with nothing to eat whatever. This was an ugly experience. There are people who do fasting cures of three weeks or more, and they say that fasting is quite pleasant after the fourth day; I do not know, never having gone beyond the third day. Probably it seems different when one is doing it voluntarily and is not underfed at the start.

I highly recommend reading his whole description of hunger, which begins on p42 of this PDF.

Anyway, I found the fourth day the hardest. Maybe I should have pushed on and it would have gotten easy by day six or seven, but by day five I felt I’d had enough.

What made you fast originally?

Come to think of it, the above passage of Orwell was the first time I’d ever heard about fasting in the modern era (I think of 1933 as being modern). It made me curious about it.

I read that book in 2007. I started intermittent fasting around 2010, via Leangains, when the refrain from everyone around me was “That’s super unhealthy!” A few years later, when the BBC began running stories like this one, several people who had previously admonished me sent them over.

Was this a dopamine fast?

Yes, or no, whichever you prefer. Names don’t matter to me.

“Dopamine fasting,” or something similar to what I’m describing on this page, has been in the news in recent years.

For some reason it seems to have caused some controversy. Possibly it’s just because of the tone of that NYT article. Or perhaps it’s part of a more general reaction against anything perceived to have originated in Silicon Valley (though as that article points out, the Buddhists and the Amish have been doing such things for much longer than tech bros).

I will respond to my (probably incorrect) understanding of the objections. If I’m missing the point, please get in touch.

Some objections seem to be to the name, e.g., “That’s not what dopamine does.” Though probably true, this is frankly irrelevant, and it’s addressed early-on in that article: “It’s more of a stimulation fast.” If you find this usage of “dopamine” to be pseudoscientific, then I understand the objection. Though if you’re confident that you know what is and is not scientific, I might refer you to my Kuhn thread.

Whatever term you use is a convenient label for a set of practices (a deliberate period of no food, screens, speech, eye-contact, whatever) that doesn’t have another name. It doesn’t matter whether it’s “scientifically accurate,” if that term even means anything in this context. I see no reason that the set of practices need have anything in common other than that you are choosing to do them together. This is about phenomenology.

Another objection seems to be that you should naturally take breaks from screens and the like, and that these breaks don’t need to be formal, ritualised, or structured. This is surely true; not everyone needs to or wants to do something like this. In like manner I have friends who remain fit despite “not exercising.” When I question them, it often turns out that they lead active lives (sometimes far more active than those who “exercise”), but they don’t think of walking/cycling/whatever as exercise, because for them it’s not structured. Fair enough, that works for some people, and other people go to the gym.

I feel the same way about a decision to take a deliberate period of abstinence. It’s just a tool; not everyone needs it.

There also seems to be a bit of a moralistic element to the backlash. This reminds me of what I’ve heard from friends who are teetotal or vegan. Of course there are proselytizers of every type, and these people are tedious, but my friends are not among them. Their decisions are personal, having nothing to do with anyone else. Still, sometimes when they say “I am vegan” or “I am teetotal,” it is taken as a judgement upon, or even as an attack against, people who are not.

Lest there be any confusion, I’m not advocating for or against fasting, “dopamine” or otherwise. I’m just reporting on my own experiences, in case they are of interest to anyone else.

As I’ve implied, I also don’t care much about what a thing is called. I have read articles about “dopamine fasting” and found people’s experiences interesting, and their experiences informed my decisions. Before going in, I thought of it as a “meditation retreat,” but afterwards, given how much I wrote, I’m starting to think of it as a “writing retreat.”

No terminology can exhaust an experience, nor does word choice matter much as long as you know what I’m talking about.

How much insulin did you use while fasting?

Because I am a type I diabetic with an insulin pump, I can tell you exactly, in units of Humalog.

For reference, on a normal day I would use around 50-60, and last Sunday (when I ate a lot) I used 93. Years ago, when I was far less careful about what I was eating, I probably used 80 on an average day.

- Monday: 39.35

- Tuesday: 16.22

- Wednesday: 11.99

- Thursday: 9.78

- Friday: 37.82

So Thursday’s 9.78 is insanely low.

On Monday I was probably still digesting food from the weekend. On Friday, I ate dinner. Still, it’s interesting to see how it dropped over the week.

How was your blood sugar?

I checked my seven-day average on my Freestyle Libre and it said 5.9 mmol/L (106 mg/dL) for the week. It said I’d been in target 95% of the time and below 3.9 (70) 5% of the time. This is very good.

How much did you exercise?

I exercised every day. I walked on average around 10km (6.2 miles) per day. The longest I walked was 14km (8.7 miles).

I also ran three times and did bodyweight exercises twice (once on the third day and once on the fifth). I was slower running, but surprisingly I managed to set a few PRs on things like pull-ups (perhaps because I was lighter). Fasting, in other words, doesn’t seem to impact physical performance as much as I might have expected.

I figured exercising when completely fasted would burn fat. But more importantly, there just wasn’t that much to do, and exercising seemed to make me less hungry and to put me in a better mood.

Did you lose weight?

Unsurprisingly, yes.

I weighed in with a lot of food/carbohydrate weight on Sunday, and with obviously zero food and some dehydration on Friday, but the scales showed me down 6.6 kg (13.9 lbs, or, in British parlance, a stone). Most of that has since come back, but I still seem to be down 2 kg = 4.4 lbs, which is a lot to lose in a week.

What was it like?

The Good

-

I read and wrote a ton (see what I read).

-

I had many, many ideas and realisations. I’ve got stacks of notes I’m still working through.

-

Without eating or cooking food, I felt like I had way more time in the day.

-

Unsurprisingly, I was a lot less distracted, a lot more aware of my surroundings, and significantly more intentional about what I was doing.

-

I found things more beautiful.

-

I felt extremely clear-headed and focused the whole week.

-

Perhaps more surprisingly, I had a lot of physical energy most of the time.

I exercised a lot.

- As a diabetic, in everyday life a certain amount of admin is involved in trying/failing to keep my bloodsugar levels (mostly) flat.

When fasting, they just stay (pretty much perfectly) flat, which saves some hassle.

-

I lost weight.

-

Time went very slowly; I felt like I had tons of it.

The Bad

-

Time went very slowly; this was sometimes agonizing or boring.

-

From the third day, I was very cold in the evenings, and could not get warm.

-

It was sometimes hard to sleep.

-

Though my blood sugars were flat, I did have to do mess with my insulin pump an annoying amount to avoid hypoglycaemia (low blood sugar) without eating anything.

-

With less to think about, small inconveniences seemed like bigger deals than they were.

-

I stayed sore longer from exercise, though it did not really seem to affect performance.

-

I was more moody in the morning than usual (and my mood in the morning is not usually great).

The cold may have been the worst part physically. It usually came on after I stopped moving for the day, sometime in the late afternoon, while I was reading. A hot shower/bath would help for an hour or so, but then my body temperature would drop again. I notice this a little after 24 hours of fasting, but it was much more intense after the third day.

I also got pretty irritable around the time I would normally “break fast,” in the early afternoon. (I don’t eat breakfast normally.) This seemed to go away once I got moving (walking or running). It’s almost like my body was satisfied with me moving and potentially looking for food. Maybe it figured I was hunting or gathering?

The Ugly

-

Any medication is much more potent.

-

I got sick on Thursday, shortly after my hunger spell.

I’m not entirely sure why, but it may well have been because I took paracetamol. It wasn’t a big deal as I had nothing but water in me. But also something to be aware of.

- It was difficult to start eating again on Friday.

I’ve read that you’re meant to break your fast with something easy; for some reason people suggest dates and yoghurt. I did not think too much about this and tried to start eating normally. My throat swelled up and I couldn’t eat for about an hour afterwards.

I assume this was my body sending a strong message that it was not ready for food yet. I waited until it went away after a while, and I was able to eat normally after that. I got full quite quickly, which I suppose is a good thing.

The Unexpected

I didn’t expect all the bad/ugly things to come from fasting; I thought that other parts of the solitude/screenlessness would be difficult, but they were not too bad.

I cared more about my physical environment, and kept it tidier than I normally do. I suppose you could say I felt more “embodied,” whatever that means. I did not feel as intensely mindful as I did in my last retreat, probably just from meditating less.

I got noticeably better at mental arithmetic. I would wonder things like, “How fast am I writing?” Then, because I had little reason not to, I would average the words on the line, multiply by the number of lines, divide the number of words by the number of minutes, etc. These are the kinds of things I used to do when I was a kid and curious. Now I think I bother with less of that, and also if I do want to do it, I can easily do it in a calculator (or more frequently in Python). The fact that I can do it so quickly in normal life means that I don’t spend much time wondering, and if I want an answer, no arithmetic is necessary.

I also greatly improved my London geography by exploring and getting lost with the A-Z. I learned alternative routes, explored new areas, and learned a lot. Reading London history also made me curious about this. I think if you’re going to do this kind of thing, or even just a digital detox/walking without a phone, I’d recommend both reading the history of your area, and taking a map.

Did you get bored?

Yes, I got bored, which was strangely sweet, and reminded me of childhood. That only happened a few times though. Mostly the reading I was doing was interesting.

Did time slow down?

Yes, definitely.

If time poverty is a problem, I felt like part of the “time top 0.01%.”

I definitely had times, especially on days 4 and 5, when I wished it was over. But I also experienced some effects like last time, where I badly misestimated time, thinking that an hour had passed when it had only been five minutes.

What about admin?

I’m not working, and I’m lucky enough not to have many responsibilities at the moment. My wife was very kind in helping out with the few things that needed doing.

I let family members and other relevant people know that they could get in contact with her if there was any emergency, and I also posted stuff on social media indicating that I’d be away.

The rest just had to wait until I was done, because obviously I was unaware of it!

I sometimes think about the fact that in any period before the late 19th century, even if a parent, sibling, or spouse died, you would only know about it immediately if you happened to be in exactly the right place. Otherwise you’d have to wait for post to arrive, and the post might have to wait for you to arrive (e.g. if you were travelling).

What did you read?

I read a lot. I’m haphazard with my reading. Even with such focus and clarity as I had this week, I could not keep myself to one book, or indeed even just to one domain.

I read just over a third of Darwin’s Origin of Species (this edition) which I loved. He’s just incredible as a complexity theorist, and he anticipates so much. I also love how he frequently says he has no time to give examples, then goes on to give the most insanely comprehensive example imaginable.

I read around half of Kim Sterelny’s Dawkins vs. Gould, which I picked up randomly in a charity shop a month or two ago. It’s an excellent, concise summary of what the two men think and why, despite so much agreement, they so vehemently differ. Though I have not yet read Gould, Sterelny’s summary already makes it palpable how much he was influenced by Thomas Kuhn, whom I’ve been tweeting about since September.

I started Alexandra Berlina’s Shklovsky Reader. I highly recommend this article if you don’t know who Viktor Shklovsky is, or especially if you do. He had an extremely crazy life.

For “fun,” I read a lot about the history of North London, where I live. Much of that was in Prickett’s History and Antiquities of Highgate, originally written in 1842, which I also picked up in a charity shop. There’s also a great chunk of Walford’s 1878 Old and New London available free online so I read a bunch of that on my Kindle. Those links are to Volume 5 which is about North London.

In that reading I learned about the practice called Swearing on the Horns, which was apparently ancient in nearby pubs in 1785, still done in 1830, and barely remembered (having fallen out of favour) by 1880 or so. By 1906 (pictured), it was already a nostalgic revival. I recommend reading about it, it’s quite funny.

I also read some of Heidegger’s “The Origin of the Work of Art”. I can’t go into my objections here, but our worldviews may well be incommensurable.

Did you avoid eye contact?

Not any more than usual. If you’re walking around a busy city, sometimes it just happens. I’m not quite sure why this is considered stimulating. It doesn’t seem so to me.

What was your system like?

Very simple. I had an A4 moleskine notebook where I did my journaling, reflections, any thoughts that I thought were worth keeping. I wrote 29 A4 pages which I estimated at around 15,000 words (using mental arithmetic, of course). That’s around 15 wpm.

I also kept several pocket notebooks around. I probably should have just kept one, but as I said I’m haphazard, and tend to grab whatever is to hand. I took a few dozen pages of notes like this, many of them lists of things to do or look up when I was back online.

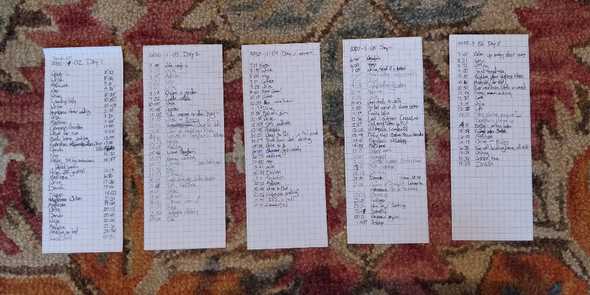

For tracking time, I have Rhodia pads like these ones (with a grid/graph paper) and I just wrote a time whenever I started an activity. If I took a break then I just wrote “break,” but that didn’t happen very often.

On the other hand I did spend a lot of time just in reveries, in thought, gazing off into the middle-distance. I didn’t track this time separately. Depending on how you regard activities like writing, I may have over-reported them above.

How did you decide what to do?

How does anyone ever decide what to do? (I’m genuinely curious.)

I suppose I just did whatever felt right. I didn’t use an alarm or stick to a schedule or anything like that, though I did follow roughly my usual daily pattern.

I normally use Complice to plan my day, then stick to that maybe 40-80%. During this week, I only planned mentally, or maybe in the journal. Usually it was like one or two things per day, like “I’ll write about this,” or “I’ll walk south today.” Since there were not many things that I could do, I mainly just switched when I felt like it.

With limited choices, and because I was tracking what I was doing, context-switching felt more expensive, and I didn’t do it as much. Often I’d feel like doing something else, remember that there was little else to do, and then wind up reading for another hour, or walking for another hour, writing more, etc.

Actually, that was one of the most jarring things about getting back online: How easy it was to switch from doing one thing to doing another. I felt like my willpower had diminished. I would exert my will to do some task, but get really easily distracted.

Are you less distracted now?

I wouldn’t say that the week gave any long-lasting protection against distractions, but it did make those distractions more acute when I returned. That makes it easier to address them, if not easier to resist them.

I have an easier time getting up and staying off social media for several hours.

What did you get out of it?

Mainly, I got a break, a reset, and a plan going forward.

Which part was most important?

I think time away from screens was the most important. I will probably do this periodically in the future, if not at the same time as fasting.

I also think I did get a reset on stimulus somehow. Now I’m fine waking up and beginning to write without checking anything online. We’ll see whether that lasts or not.

What was it like emotionally?

It was a roller coaster. Like any long period of solitude, it teaches you that most of your moods are self-generated, even when conditions outside yourself change little. This was what I found on the last retreat and the ten-day Goenka retreat I did in 2018.

I would say that because I was writing more (which can take the form of venting) and meditating less (which tends to cause weirder experiences), I was probably less emotional than on other retreats I’ve been on.

Still, there were the usual ecstatic highs, depressed lows, moments of self-doubt (“Why am I doing this?!”), angry moments, sad moments. Overall, though, and despite all that, I would say that I had less emotional turmoil and self-loathing than I do on a normal week.

Another thing I noticed was that my regret seems tied to social interactions. I generally think that I’m a regretful person, that I just naturally wake up with regrets from whatever I did the day before. By being completely isolated, I realised that it’s often things I say in conversation that I regret, whether or not that’s warranted. Evidently if I don’t interact with anyone, I don’t get regretful (though I do still get moody).

Any breakthrough insights?

Because I wasn’t meditating as much, I didn’t feel like I made much progress with wisdom.

Mostly, I felt like I got clarity about how I needed to structure my days, and what I would do about the writing that I’m working on.

I have yet to read my voluminous journaling, so I may update this section later.

How was your mood?

I noticed that I was less despondent.

Anything else?

I did notice, especially on day 2-3 when I was meditating a few more hours than I usually do, that I was having more prediction errors.

This came in the form of trouble writing (I’d sort of become too conscious of a letter or spelling, and lose fluency).

I also saw a few things that weren’t there. That probably makes it sound more dramatic than it really was. I would look, and think I saw a bird of prey perched in the birch, then realise that no, actually that was just a branch. Or I would think I’d seen a cat where there was in fact no cat. It was the kind of thing that can happen in everyday life, but it was more frequent.

I saw more patterns in nature, and was generally more absorbed by it, for example watching the wind move the leaves of trees.

What did you most look forward to afterwards?

Eating food and talking to my partner. In normal life I probably also would have looked forward to seeing friends, but I was coming out of retreat into a new lockdown, so I knew that wouldn’t be a thing.

How did the planning go?

You’re reading this as a result. I came up with a pageful of rules I wanted to follow, one of which is to write 2,000 words immediately upon waking on weekdays, and to publish five blog posts per week.

I’ve been very uncertain about how to proceed with my writing. After over a year of thinking within my Zettelkasten, I have hundreds of ideas, but I have not been publishing many of them. I am also in principle (and was, in practice, until March) working on a novel. Intuitively I know that the work in the Zettelkasten relates to the novel, but I don’t yet know how.

I wanted to think through and consider many possible options. For example, I could resume my editing of the previous draft of the novel, scrap it and rewrite the whole thing, double-down on the Zettelkasten, or commit to public writing for some period before returning. In the end I chose the last.

I felt that silence, and diligent note-taking, was the best way to do this. On Friday, I felt I had a solid plan.

Any regrets?

I should have got a haircut before this lockdown.

I should also have made sure that I’d done a more thorough “admin catch-up” before beginning, because I’d forgotten to send several emails.

Finally, I should have written down friend’s addresses on paper so that I could have sent them letters more easily. For one friend who doesn’t live far away, I hand-delivered a letter.

Did you get what you wanted from this experience?

Overall, yes.

Would you do it again?

Probably not in exactly this way. In a way, I did six things at once: I fasted, I did a digital detox, I kept a vow of silence, I wrote a lot, I read a lot, and I meditated more than usual. I think in the future I would probably divide these things up rather than doing them all at once.

I actually think that the intense focus I get from fasting would be better used when I can do more things. I feel like I could have been super productive at certain things online during a five-day fast.

Conversely, both writing and meditating are hard, and probably even harder without food. So if I really wanted to focus on a week of writing or meditating in the future, I would still do most of that stuff fasted in the morning, but I would eat later in the day so I could continue with the same intensity the next day. It was getting hard to keep up the pace of reading/writing/meditating by day five.

Would you recommend this to others?

I would absolutely recommend that you try this for 24 hours. I think it would give you a lot of the insights without too much of the pain.

I don’t think I’d recommend exactly what I did to anyone. If you’ve read this far, you probably understand which parts appeal to you and which don’t.

Overall it was good

If it’s not clear from the above, I’m very glad I did this, even if I would not do it in precisely the same way again.

Thanks for reading. If you liked this, please consider signing up for my infrequent newsletter. I’d also love to have you at the Asceticism salon or to hear from you on twitter.

I'm Bryan Kam. I'm thinking about complexity and selfhood. Please sign up to my newsletter, follow me on Mastodon, or see more here.